Originally Published in The Huffington Post

As this brown, bearded Muslim was getting ready to pick up his Thanksgiving turkey order from a local Boston Market, news broke of racist graffiti in New York city.

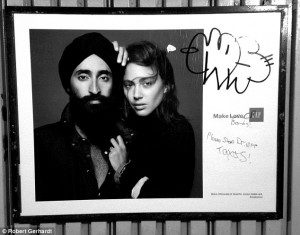

Gap had recently launched a holiday ad campaign featuring diverse models. One such ad showcasing the famous designer and actor Waris Ahluwalia, a Sikh American, had been vandalized, its “Make Love” caption changed to “Make Bombs,” in the New York City subway system. What followed defied the norm: Arsalan Iftikhar, founder of the TheMuslimGuy, tweeted a picture of the racist vandalism, and Gap not only noted it but quickly elevated the visibility of the image by setting it as their Twitter background, for over 315,000 of their followers to see. Then CNN projected the message to millions of its viewers.

I am thankful for this America where the chain of solidarity against hate is becoming stronger, by the day, it seems, by growing new links. What has been the Sikh and Muslim communities’ fight for years was joined by Gap and CNN. What had been a lament in temples and at dinner tables for years made it to social and mainstream media on the eve of Thanksgiving.

But let’s not get overly excited. This is not the norm. As long as you are brown and bearded, Sikh or Muslim, your reality is different. You are not used to being protected, let alone elevated. You assimilate in this America while trying to educate the other America.

In that America vandals spray paint a mosque on the night of Bin Laden’s death with “Osama Today, Islam Tomorrow” and get away with it; Ann Coulter asks all Muslims to “take a camel” and remains a conservative darling; Pamela Geller advises in her Subway ads, “In any war between a civilized man and the savage, support the civilized man. Support Israel. Defeat Jihad,” and keynotes one mass gathering after another.

In that other America the Sikh community suffers not just verbal but armed assaults. The tragic shooting of six Sikh worshipers in Wisconsin in 2011 represents a trend dating back a decade. No more than five days after 9/11, a 49-year-old Sikh gas station owner, Balbir Singh Sodhi, was shot and killed in Mesa, Ariz., only because he was brown and bearded. This September a Sikh professor at Columbia University was beaten by over a dozen men yelling, “Get Osama.” In other words, he looked like a Muslim to them.

In that other America, when a small, Florida-based conservative group protests against a reality TV show titled All-American Muslim, featuring five Muslim families from Dearborn, Mich., home improvement giants like Lowes cave to the pressure and pull their ads. In that America the movies typically showcase a Mexican girl as a nanny, an Indian man as a convenience store owner, a black man as a violent criminal, and a Muslim man as a cab driver.

And those responsible for creating or reinforcing such stereotypes are hailed as authors, activists, artists. Putting it differently, the cruder and the more anonymous a racist comment, the greater the public outcry.

This is not to ignore the fact that there are extremist elements hiding within the Muslim community. There are. And many of us, including Sikh and Muslim Americans, are sick and tired of them, and we’re committed to rooting them out. Muslims are at the forefront of providing tips to the FBI whenever they notice suspicious activity. It was a Muslim who tipped the NYPD about the SUV of Faisal Shahzad, the failed Time Square bomber. Even before the arrest of the second Boston bomber — who was neither brown nor bearded — his Muslim uncle, Ruslan Tsarni, angrily condemned his nephews’ actions and called them“losers.” Muslim author and activist Asra Nomani wrote, “Muslims have a problem. Uncle Ruslan may have the answer.” I have made so many such calls for this kind ofintrospection that some of the brown, bearded Muslims have called me a “sellout.”

This sentiment goes beyond words. It’s backed by robust action by many Muslim and Sikh communities. My own group, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, has done exceptional outreach to dispel such myths by organizing the annual “Muslims for Life” campaign, where we annually raise over 10,000 units of blood to commemorate the victims of 9/11.

“Hate is a part of life, and you’d better learn to deal with it.” That is what I plan to tell my 12-year-old son when we enjoy this year’s Thanksgiving dinner. He couldn’t choose his skin color or his country of birth. Whether he chooses to keep a beard or not will depend upon the values I teach at home and the truth that he learns on the street. “Make Bombs” demonstrates the gap that separates those two realities today.

If others follow what Gap started, that gap may morph into a bridge by the time my son picks up his own family’s Thanksgiving turkey order years from now… as a brown, potentially bearded American man.