Originally Published in the New Haven Register

My name is “Sohail.” Based on my Indian ancestry, my name is pronounced just the way it’s spelled.

But because I’m a Muslim and my name is derived from Arabic, it’s technically pronounced “Su-hayl.”

Try explaining that to someone on the other line when you’re trying to phone in a rushed order for Chinese takeout. So out of convenience, I will occasionally go by “Su” — my self-appointed Chinese name.

In high school I was president of my Spanish club, and my Spanish name was “Salvador.” It means “Savior,” which as a teenager I found to be really cool.

As we move into Christmas, the thought of names calls into question an interesting legal proceeding that caught national attention this fall. In August, Tennessean Child Support Magistrate Lu Ann Ballew was asked to deliberate in a dispute between the parents of an 8-month-old boy over whose surname the infant would assume. Instead of simply ruling on the issue, the judge also ordered the child’s first name of “Messiah” to be changed to “Martin.” Her rationale was that there could only be one Messiah, and she added, “That person is Jesus Christ.”

So what if a zealous judge overstepped her legal boundary by renaming a child? Why did a decision ultimately over semantics evoke such an intense visceral response among so many people — including yours truly?

Firstly, the incident bespeaks of ignorance on multiple levels. Quick fact check — most modern-day Christians believe Jesus is literally the son of God and thus himself a god. The judge took offense because she felt it was sacrilegious to assign a child the name of God. But that’s just one viewpoint.

Among Christians in Latin America, on the other hand, Jesus is actually a common name (pronounced “Hesoos”). Jesus, pronounced “Isa” in Arabic, is also popular among Muslims, who revere him as a noble messenger and figuratively as a son of God. As a result, there are thousands of Jesuses in the world today. Even if the judge worked overtime and into the winter holiday, she still wouldn’t have enough time to undo all of those names.

Another question raised by Ballew’s final comments is whether there is only one Messiah. And who is the Messiah? Of course, the answer ultimately depends on which faith you subscribe to. Another fact check — most Christians and Muslims do believe that Jesus is a Messiah and that a Messiah will return at a distant time, termed the “Latter Days.” But not everyone is expecting the return of the same Messiah from 2,000 years ago. For example, my religious group the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community believes that our founder — Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian (1835-1908) — is the awaited Messiah, only spiritually-speaking that is. The advent of a person carrying the same name and title as a predecessor is analogous to an account from Jesus in the Old Testament where he indicates that John the Baptist was the second coming of Elijah. Not literally though. Different person. Same mission. In today’s global village, the judge should be aware that according to some people there could indeed be more than one Messiah.

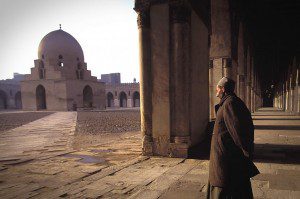

The second reason why the judge’s decision struck a chord is that it was a clear violation of our Founding Fathers’ principles of separation of church and state. Arguably I may cherish these values more than the next person, primarily because members of my Muslim sect in a country like Pakistan are by constitutional law banned from calling themselves “Muslims,” or even calling their mosques as “mosques.” In a statement that comes straight out of the Pakistani penal code, Ahmadis who so much as “pose as Muslims” are punishable by a three-year jail sentence. Call it sensitive, but I think that even relatively minor infractions like renaming a child on the basis of basic doctrinal beliefs should not be taken lightly. They break away from our fundamental tenets of keeping religious differences out of governance and could lead to dangerous precedents. Sadly, my Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan knows well how state-sponsored religious extremism can put a choke-hold on an entire nation.

A third reason to react to the involuntary name change is that a person’s name carries an identity and usually confers a meaning. Parents often give their children the names of people they love. That’s why among Muslims it’s no surprise that “Muhammad” — taken from the name of the Holy Prophet of Islam — is the most commonly given name. By sheer numbers, it’s probably also the most popular name in the world, and, in recent years, in England and Wales, as well. Messiah literally means “anointed” or a “deliverer.” Nice attribute to have for a name. A young Messiah who reflects upon the meaning of his name might feel motivated to become a good citizen, or maybe even a fair judge.

As for me, I think I’ll mostly stick to the spelling and pronunciation of the name my parents gave me, which is “Sohail.” Among several meanings, it means “easy-going.” Other than when I write about coercive name changing, do I live up to my name? I’ll let my wife and kids decide.